Blog by Professor Helle Krunke, CECS, Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen

How similar are the Nordic constitutional systems? Which common roots and legal-historical developments do they share? How do the Nordic constitutions regulate institutions and division of powers, judicial review of legislation, parliamentary control of the executive and human rights? Do the EU and international human rights conventions draw the Nordic constitutional systems closer to each other or further apart? These are some of the questions, which the book attempts to answer through a comparative lens.

While analyzing the mentioned questions, the book contributes to the general academic discourse on a.o. constitutional change, constitutional design, constitutional identity, constitutional culture and constitutional interpretation. One of the fascinating aspects of the book and one of the reasons for writing the book is to compare the impact of the fact that the Danish Constitution has not been revised since 1953, while the other Nordic Constitutions have been amended more recently. How does this play out comparatively especially in light of EU/EEA membership and international human rights conventions such as the European Convention of Human rights (ECHR)? In this blog we will touch upon a few of these aspects.

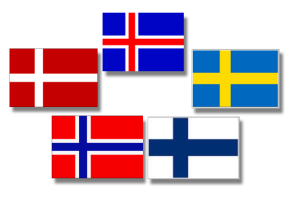

Only three Nordic countries, Denmark (1972), Sweden (1994) and Finland (1994) are members of the EU, while two Nordic countries, Norway and Iceland, are only EEA members. All the Nordic countries have incorporated the ECHR into their national legal systems. How does this impact the Nordic Constitutions? If we start with the EU, one interesting aspect is that the constitutions of Sweden and Finland now mention membership of the EU in their Constitutional text, while the Danish Constitution does not. The latter might seem reasonable since the Danish Constitution has not been amended since 1953. However, one might turn the argument around and ask why the Constitution has not been amended in light of EU membership since 1972. Norway and Iceland do not mention the EEA cooperation in their Constitutions. Again, this might seem obvious since EEA membership is less binding and not supranational like EU membership. However, it might also be interpreted as the Nordic East/West divide, which traditionally shows in other areas. Finland and Sweden openly recognize the importance of their EU membership, while it is ‘hidden away’ in the Danish Constitution and as regards the EEA in the Norwegian and Icelandic constitutions. Another, interesting discussion is how distinct the impact of the division between EU membership and EEA membership is in reality. Many EU-principles such as supremacy and direct effect exist as quasi-legal principles in EEA-law and there is little doubt that the EU has a significant impact on the legal systems of Norway and Iceland even though they are not fully members of the EU.

If we move on to the ECHR, it has clearly had an impact on the content of the constitutional design of the Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian and Icelandic Constitutions. The Danish Constitution on the other hand, has no sign of the convention. The Danish human rights catalogue stems from 1953 and some provisions all the way back to the original Constitution from 1953. What does this mean in practice? Since the ECHR is incorporated into the Danish legal system, the Convention plays a very important role. In many cases, the Convention and case law from the European Court of Human Rights provide a stronger and more modern protection of human rights than the Constitution itself. This means that the human rights protection in Denmark is in reality not that different from the human rights protection in the other Nordic countries (though some Nordic countries have recently codified new rights e.g. a protection of nature). However, there might be a difference in the level of protection (legislative ctr. constitutional). An interesting impact of the mentioned difference is also, that the Danish Constitution might live a more quiet life in practice, since court cases will normally build on the ECHR. Some might say that the practical importance of the Constitution fades as it grows older.

Finally, if we focus on legal culture and not just content, the EU and the ECHR seems to have had more impact on the legal culture of some Nordic countries such as Finland than on others such as Denmark. The Nordic Constitutions have not traditionally focused on general principles and values. However, for instance the Finnish Constitution now clearly reflects general values and principles already in Article 1. Furthermore, the institutional design has been changed in such a way that Finnish courts can now conduct a constitutional review of legislation. This was not possible before Finland entered the EU and amended its Constitution. The country has a strong tradition for ex ante review.

Our comparative study analyses five Constitutions in countries, which clearly have much in common as regards values and culture. However, these values and this culture does not necessary show in the constitutional texts. For instance gender equality has a long and strong tradition in all five Nordic countries. However, it is most clearly reflected in the text of the Finnish, Swedish and Icelandic Constitutions. In Denmark it is mainly regulated by legislation.

In the end of the book, we attempt to answer whether the Nordic constitutional systems are moving closer to each other or further apart. This is a very complex question to answer because of all the different processes, which are taking place at the same time. In the concluding chapter, we provide an overview of the main features of the Nordic constitutions, the areas where the traditional East/West divide still exists and the areas where we find differences across the Nordic countries and the East/West divide. Furthermore, we provide an overview of the impact of EU/EEA law and international human rights conventions. Finally, we combine everything and analyse how all these processes play out viewed at the same time. Do the Nordic constitutional systems countries move closer or further apart? The answer you will find in the book…

The book is volume 23 in the series Hart Studies in Comparative Public Law.

For further information see: https://www.bloomsburyprofessional.com/uk/the-nordic-constitutions-9781509910946/